Fungi

When fungi start to appear at the end of July, on the forest paths, in the old thickets down by the lake, under the birch trees, it always comes as a surprise.

Their shapes are completely alien; clubs, hats, spikes, parasols, but only one word really applies: fungi. Just as unclear what they actually consist of. Where was the substance that caused them to grow?

In the ground? In the air?

Between the end of July and the end of October it is as if an other, perhaps an older, vegetation were trying to conquer nature, and is then forced to retreat once more.

The starry sky, the staring of the galaxies.

The stubborn capacity of the universe to maintain unheard-of distances, as opposed to our just as eager attempts to see the world as small, as surveyable, frequentable for signals and observations.

The quantum logic of physics and chemistry. The same thing: the stubborn refusal of matter to be anything else than probabilities, shadows that play over bare rocks in the sunset, sudden gusts of wind that pass through a solitary aspen in the coppice yet leave the aspens next to it completely still. And our stubborn eager struggle for a substance, particles, individualities that refuse to exist in real physics.

This world of distances and shadows and random leaps between spectral lines, this frightening silent dance is what I mean by the silence of the world before Bach.

Human existence must thus be conceived as something enacted on a narrow spit of land between one sea and the next sea.

That narrow strip of knowledge between two vast realms of ignorance, deep as unconsciousness or death.

So how do we know if that narrow strip lies still, that it is not constantly in motion, is fast drifting in a maelstrom?

A spit of land. A strip of land. What speaks for it being so large? Perhaps what we are now talking about is as thin as the membrane of a rainbow, where the colours waver and move in Newtonesque interference patterns?

It just came to me, one says about the great, the liberating ideas in one’s life, by which we mean from within.

The world outside us is like a sea, or a space that loses itself in black transfinite depths.

The accounts of astronomers have long since accustomed us to gain at least a diffuse picture of this.

It is harder though to accept the idea of an inner space that is not us.

The existence of historical schemata on the basis of which we unknowingly act, categories of concepts which we acquire without realising that they exist, and the sudden shifts and glides in these systems that every hundred years can take place and suddenly demonstrate how random they are, provide us with an inkling that these depths actually exist.

In old books of physics, 19th century books of experiments with lithographs, 18th century ones with woodcuts as well as those even older, one can see just how unsure and changeable the landscape of natural science is.

Earlier, electricity was thought to be a fluid and from that period we still have the Leyden jar, once light was thought of as a ray than could be broken and sifted, since when there are lenses and prisms.

Like flocks of birds in the autumn, hypotheses can sudden break out from an area and roam into another one, all questions can wander off from a landscape into another one where other instruments and other hypotheses flourish.

Knowledge roams through the world without ever wanting to stay in one and the same place for a sufficient length of time to take up residence there.

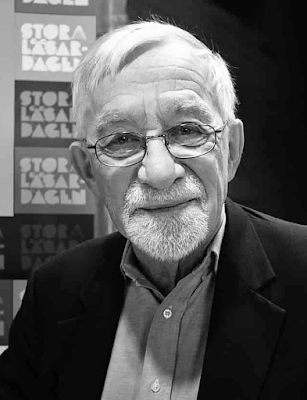

(Lars Gustafsson, Valda Skrifter 1, pp.389-391)

The silence of the world before Bach

There must have existed a world before

the Trio Sonata in D, a world before the A minor Partita,

but what was that world like?

A Europe of large unresonating spaces

everywhere unknowing instruments,

where Musikalisches Opfer and Wohltemperiertes Klavier

had never passed over a keyboard.

Lonely remote churches

where the soprano voice of the Easter Passion

had never in helpless love twined itself round

the gentler movements of the flute,

gentle expanses of landscape

where only old woodcutters are heard with their axes

the healthy sound of strong dogs in winter

and – like a bell – skates biting into glassy ice;

the swallows swirling in the summer air

the shell that the child listens to

and nowhere Bach nowhere Bach

skating silence of the world before Bach

(Lars Gustafsson, Valda Skrifter 1, p.369)